Infographic - assessment of youth and rangatahi wellbeing and access to services

Published June 2024.

Te Hiringa Mahara - Mental Health and Wellbeing Commission monitors the status of mental health and wellbeing for the people of Aotearoa, New Zealand. We also monitor mental health and addiction services. As an entity we have a strategic priority to address the determinants of mental health and wellbeing to achieve equitable outcomes.

This infographic primarily presents findings from our quantitative assessment of mental health and wellbeing among young people and rangatahi Māori, using the He Ara Oranga framework. It also presents key service monitoring findings for young people against the He Ara Āwhina framework.

We intend for this information to be used to inform policy and system responses to promote mental health and wellbeing for young people and rangatahi Māori in Aotearoa, New Zealand.

As well as viewing on this page, you can download in these formats:

Give us feedback: we welcome comments or suggestions about this infographic. Get in touch: Contact us

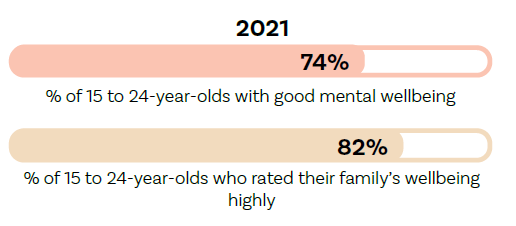

Most young people reported good mental wellbeing and rated their family wellbeing highly in the four months preceding the COVID-19 Delta variant outbreak in August 2021 (however, mental wellbeing among young people may have dropped later in 2021). (1)

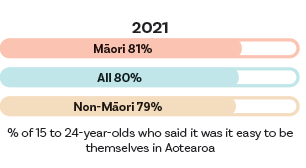

Four out of five young people felt it was easy to be themselves in Aotearoa. This was consistent for Māori and non-Māori.

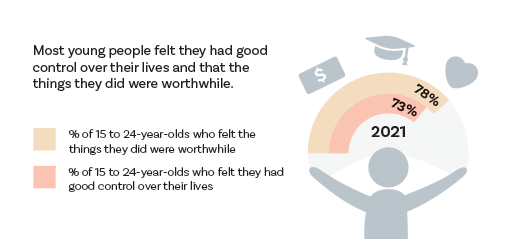

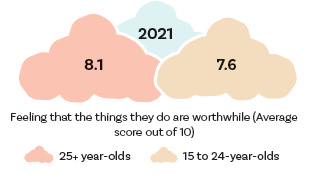

Most young people felt they had good control over their lives and that the things they did were worthwhile.

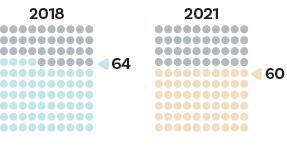

Average youth mental wellbeing scores dropped between 2018 and 2021, continuing a longer-term decline. (2)

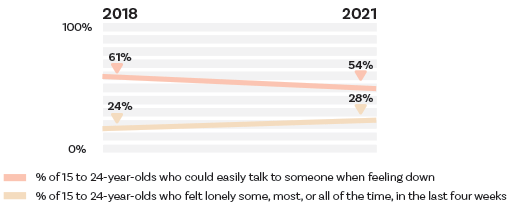

Loneliness was high among young people, compared to older age groups, and may have worsened in 2021, alongside a decrease in the proportion of young people who felt they could talk to someone if they felt down.

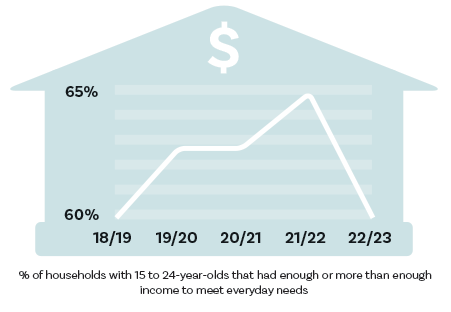

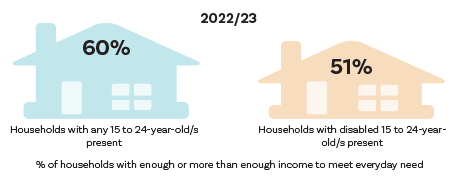

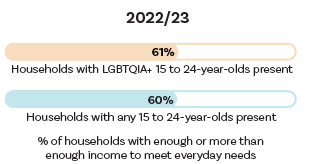

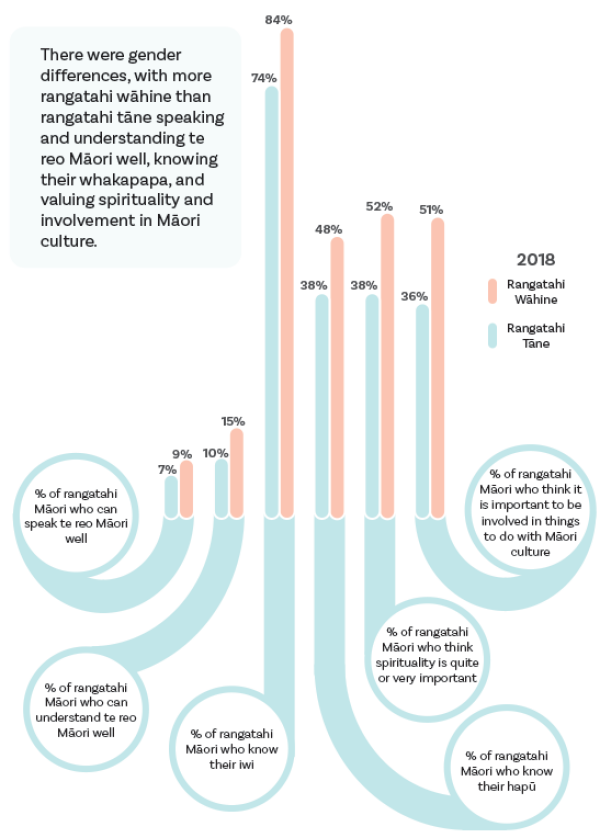

From 2018/19 to 2021/22, income adequacy improved for households with young people present. It then dropped in 2022/23, coinciding with cost-of-living increases. (3)

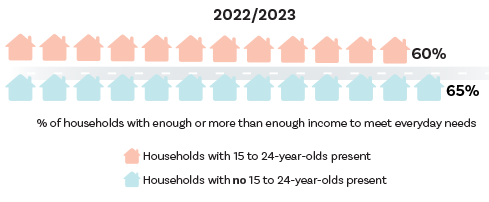

Households with young people were less likely to have enough income to meet everyday needs.

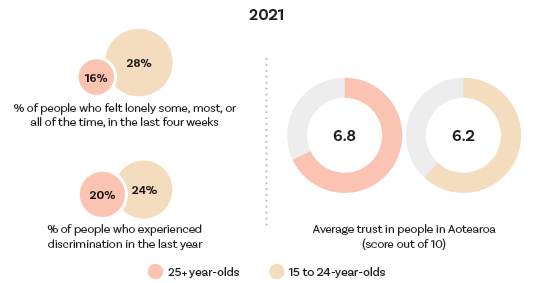

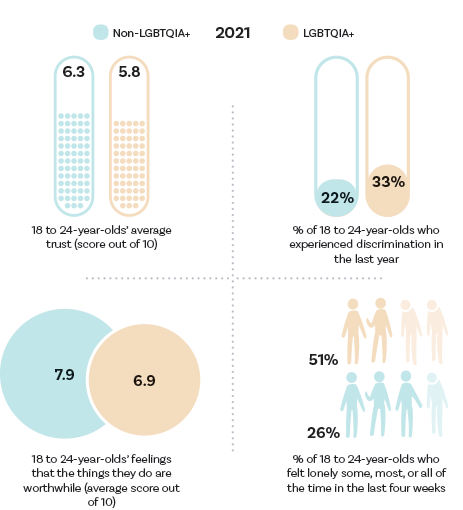

Young people were much more likely to experience loneliness, more likely to experience discrimination, and less likely to have trust in other people.

Young people were less likely to feel that the things they did were worthwhile.

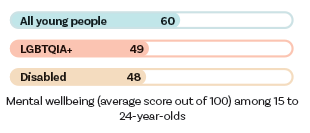

On average, disabled and LGBTQIA+ young people had poorer mental wellbeing than other young people. (4)

Disabled young people were less likely to live in households with adequate income, had less trust in people, experienced more discrimination and loneliness, and were less likely to feel that the things they did were worthwhile.

Household income adequacy and trust in people were not significantly different between LGBTQIA+ and other young people. But LGBTQIA+ young people experienced more discrimination, were more likely to feel lonely, and were less likely to feel that the things they did were worthwhile.

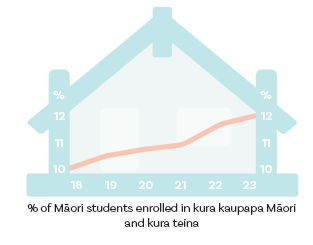

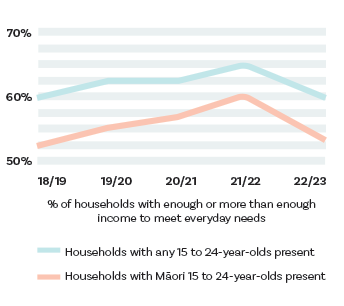

The proportion of Māori students enrolled in kura kaupapa Māori is growing steadily, continuing an upward trend since 2015.

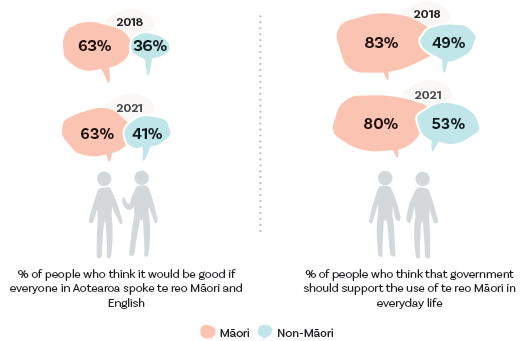

Support for te reo Māori is high among Māori and is increasing among non-Māori.

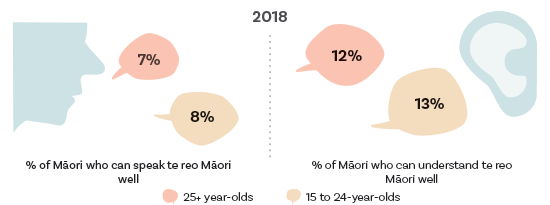

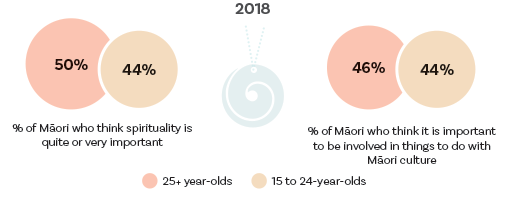

Rangatahi Māori were as likely as older Māori to speak and understand te reo Māori well...

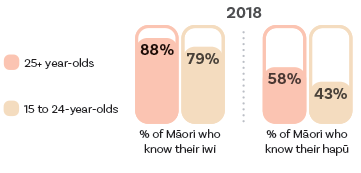

...however, fewer rangatahi Māori knew their whakapapa.

Compared to older Māori, rangatahi Māori were less likely to think spirituality was important, but almost as likely to think it was important to be involved in Māori culture.

There are inequities in material wellbeing wellbeing for rangatahi Māori. Fewer Māori families have enough income to meet everyday needs and the gap between Māori and non-Māori has persisted over time.

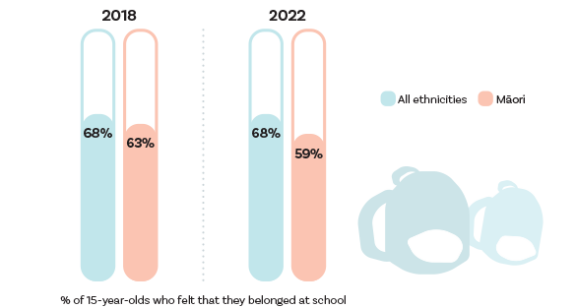

Fewer Māori school students felt that they belonged at school.

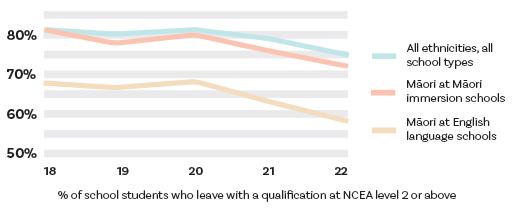

Fewer Māori achieved qualifications at NCEA level 2 or above but NCEA level 2 achievement was higher for Māori who attended kura kaupapa. Across all ethnicities and school types, NCEA level 2 achievement trended downwards in 2021 and 2022.

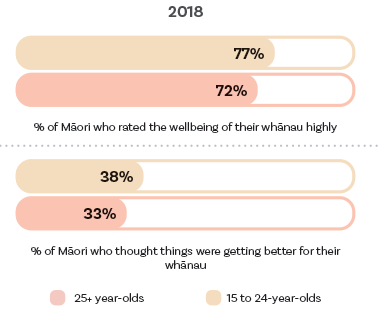

More than three quarters of rangatahi Māori rated their whānau wellbeing highly in 2018 and nearly 40% said that things had got better for whānau over the last year.

On average, rangatahi were more optimistic about whānau wellbeing than older Māori.

The He Ara Oranga framework describes what wellbeing looks like for people and whānau in Aotearoa New Zealand, at a population level, while He Ara Āwhina describes an ideal mental health and addiction system. These frameworks are designed to work together, acknowledging the critical contribution of the mental health and addiction system to achieving broader wellbeing outcomes by providing services and support where needed.

In our report Kua Tīmata Te Haerenga | The Journey has Begun, we use He Ara Āwhina to monitor access to mental health and addiction services and the service options available to people. Below we present the key findings for young people.

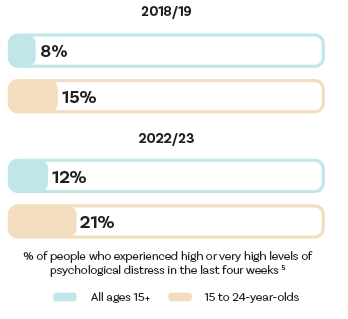

One in five 15 to 24-year-olds experienced psychological distress in 2022/23. This is higher than other age groups, and it has risen over time. (5)

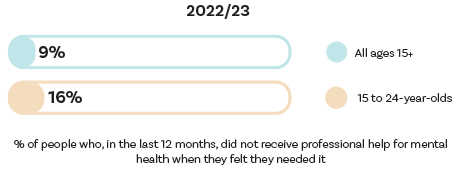

Young people are less likely to be able to get professional help for their mental health needs compared to other age groups.

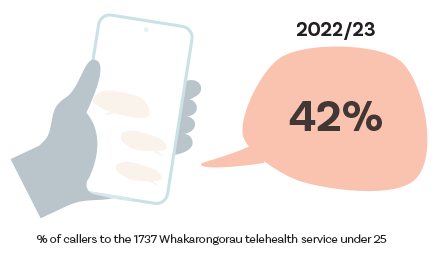

Telehealth services can provide accessible help for young people in addition to a wide range of digital tools, online platforms, and social media.

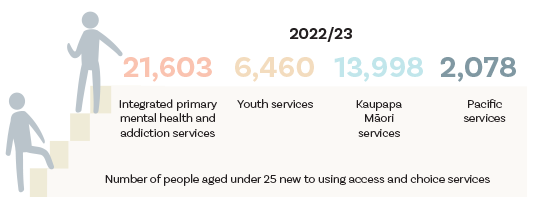

Access has increased since 2020 with four service types now available- Integrated Primary Mental Health and Addiction Services, Kaupapa Maori, Pacific and Youth services. These were used by thousands of young people in 2022/23.

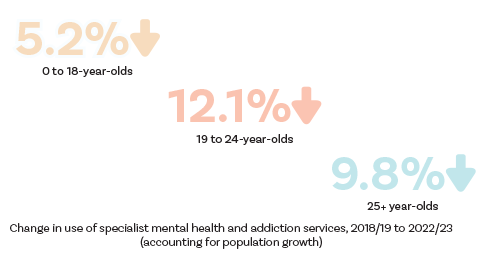

Access rates of young people under 25 are decreasing. The rate of young people aged 19 to 24 using specialist services has decreased more than other age groups over the last 5 years.

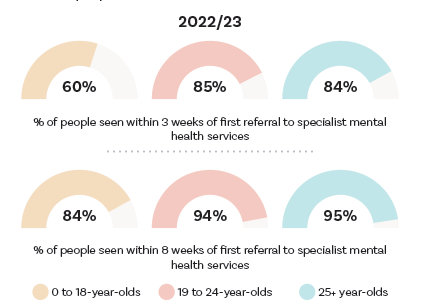

Children and adolescents aged 0-18 years wait longer for specialist mental health services than older people.

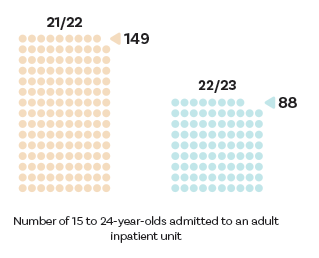

Young people have often been expected to fit into adult services, including inpatient care in adult facilities. While young people continue to be admitted to adult inpatient units, the number has fallen in the last year.

The He Ara Oranga wellbeing outcomes framework presents a set of long-term mental health and wellbeing outcomes, at a population level, based on 'shared' and 'te ao Māori' perspectives. The shared perspective outcomes that we used to assess wellbeing for young people are:

| Outcomes concept | Indicator | Source |

| Being safe and nurtured | The proportion of 15 to 24-year-olds who felt lonely some, most, or all of the time in the last four weeks Average 15 to 24-year-olds’ trust in other people (how much they report trusting most people in New Zealand, on a scale of 0 to 10) The portion of 15-year-olds who felt that they belonged at school |

GSS

GSS

PISA |

| Having what is needed | The proportion of households with 15 to 24-year-olds present that said their income was enough or more than enough to meet their everyday needs | HES |

| Having one’s rights and dignity fully realised | The proportion of 15 to 24-year-olds who report experience of discrimination in the last year | GSS |

| Healing, growth and being resilient |

The proportion of 15 to 24-year-olds with good mental wellbeing; average mental wellbeing scores (6) The proportion of 15 to 24-year-olds who rate their family’s wellbeing highly (7) The proportion of 15 to 24-year-olds who say it would be easy or very easy to talk to someone if they felt down or a bit depressed |

GSS |

| Being connected and valued |

The proportion of 15 to 24-year-olds who think it is easy to be themselves in Aotearoa | GSS |

| Having hope and purpose |

The proportion of 15 to 24-year-olds who felt they had good control over their lives (8) The proportion of 15 to 24-year-olds who felt the things they did were worthwhile; average worthwhileness scores (9) |

GSS |

The te ao Māori perspective outcomes that we used to assess wellbeing for rangatahi Māori are:

| Outcome concept | Indicator | Source |

| Tino rangatiratanga me te mana motuhake | The proportion of Māori students enrolled in kura kaupapa Māori The proportion of Māori 15 to 24-year-olds who think spirituality is quite or very important The proportion of Māori 15 to 24-year-olds who rated the wellbeing of their whānau highly (10) |

MoE TK TK |

| Whakaora, whakatipu kia manawaroa | The proportion of people who think it would be good if everyone in Aotearoa spoke te reo Māori and English The proportion of people who think that government should support the use of te reo Māori in everyday life The proportion of Māori 15 to 24-year-olds who can speak te reo Māori well The proportion of Māori 15 to 24-year-olds who can understand te reo Māori well The proportion of Māori 15 to 24-year-olds who think it is important to be involved in things to do with Māori culture |

GSS GSS TK TK TK |

| Whakapuawaitanga me te pae ora | The proportion of Māori school students who leave with a qualification at NCEA level 2 or above |

MoE |

| Whanaungatanga me te arohatanga | Not reported here. Key indicator is the proportion of Māori 15 to 24-year-olds who find it easy to find someone to support them in times of need | TK |

| Wairuatanga me te manawaroa |

The proportion of Māori 15 to 24-year-olds who know their iwi The proportion of Māori 15 to 24-year-olds who know their hapū |

TK |

| Tumanako me te ngakaupai |

The proportion of Māori 15 to 24-year-olds who thought things were getting better for their whānau (11) | TK |

1. Results from the ‘What About Me’ survey indicate that 58% of 13 to 18-year-olds had good mental wellbeing in the period June to November, 2021.

2. Sutcliffe et al (2023) Rapid and unequal decline in adolescent mental health and well-being 2012–2019: Findings from New Zealand cross-sectional surveys. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 57(2) 264–282

3. Stats NZ (2024) Household living-costs price indexes: December 2023 quarter.

4. We defined LGBTQIA+ as survey respondents who identified as having a sexuality that was not heterosexual, a gender that was not the gender they were assigned at birth, or a gender assigned at birth that was not male or female. For General Social Survey respondents, this data was only available for people aged 18 years and over.

5. High or very high psychological distress is defined as a score of 12 or more on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale.

6. We define good mental wellbeing as a score of 52 or more (out of 100) on the WHO-5 wellbeing index.

7. We define high family wellbeing as a response of 7 or more to the question: “where zero means extremely badly and ten means extremely well, how would you rate how your family is doing these days?”

8. We define good control as a response of 7 or more to the question: "where zero is ‘no control at all’ and ten is ‘complete control’, how much control do you feel you have over the way your life turns out?"

9. We define feeling that the things they do are worthwhile as a response of 7 or more to the question: "Where zero is not at all worthwhile, and ten is completely worthwhile, overall, to what extent do you feel the things you do in your life are worthwhile?"

10. We define high whānau wellbeing as a response of 7 or more to the question: “where zero means extremely badly and ten means extremely well, how would you rate how your whānau is doing these days?”

11. Based on responses to the question: ‘Compared to 12 months ago, overall, would you say that things are currently better, worse or about the same for your whānau

How we assessed the mental health and wellbeing of young people and rangatahi Māori

Drawing on expert advice, we selected a set of 30 youth-relevant indicators from the 49 He Ara Oranga indicators published in the 2021 Te Rau Tira Wellbeing Baseline Report. These indicators draw on data from the General Social Survey (GSS), Te Kupenga (TK), the Household Economic Survey (HES), the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), and Ministry of Education administrative data (MoE).

We extracted GSS, TK and HES data from the Integrated Data Infrastructure (IDI) and used published PISA and MoE statistics.

After exploring the data, we chose 24 of the indicators as headline findings for this infographic. Some indicators use data from the 2021 GSS, which was curtailed due to the COVID-19 Delta

outbreak and has a smaller than usual sample size (3,484 people compared to around 8,800 for the 2018 GSS). The 2021 GSS sample was representative of geographic areas and demographic groups, so results are not thought to be biased. TK was lst conducted in 2018. Data from the from the GSS, TK and HES are not official statistics.

They have been created for research purposes from the IDI which is carefully managed by Stats NZ. For more information about the IDI please visit https://www.stats.govt.nz/integrated-data.,/p>

Data on youth access to mental health and addiction services

We describe how we monitored access to mental health and addiction services using He Ara Āwhina in our report Kua Tīmata Te Haerenga | The Journey has Begun. Key youth indicators from that report were selected for this infographic. These indicators use data from The New Zealand Health Survey, Te Whatu Ora's Programme for the Integration of Mental Health data (PRIMHD), and Whakarongorau national telehealth service, and the Access and Choice programme.